I timed my annual trip to Arizona to visit my mom (writer Alison H. Deming), to intersect with Desert X 2021, the third iteration of a biennial exhibition in California’s Coachella Valley (this year curated by César García-Alvarez and Neville Wakefield). In this year’s version, work by 13 artists is installed in distinct locations throughout Palm Springs. The stated intention of Desert X is to have the work engage with the desert as a “place and idea,” and the most successful work approaches this goal by considering the colonizing histories of the desert landscape and futures that revision our relationship to the land.

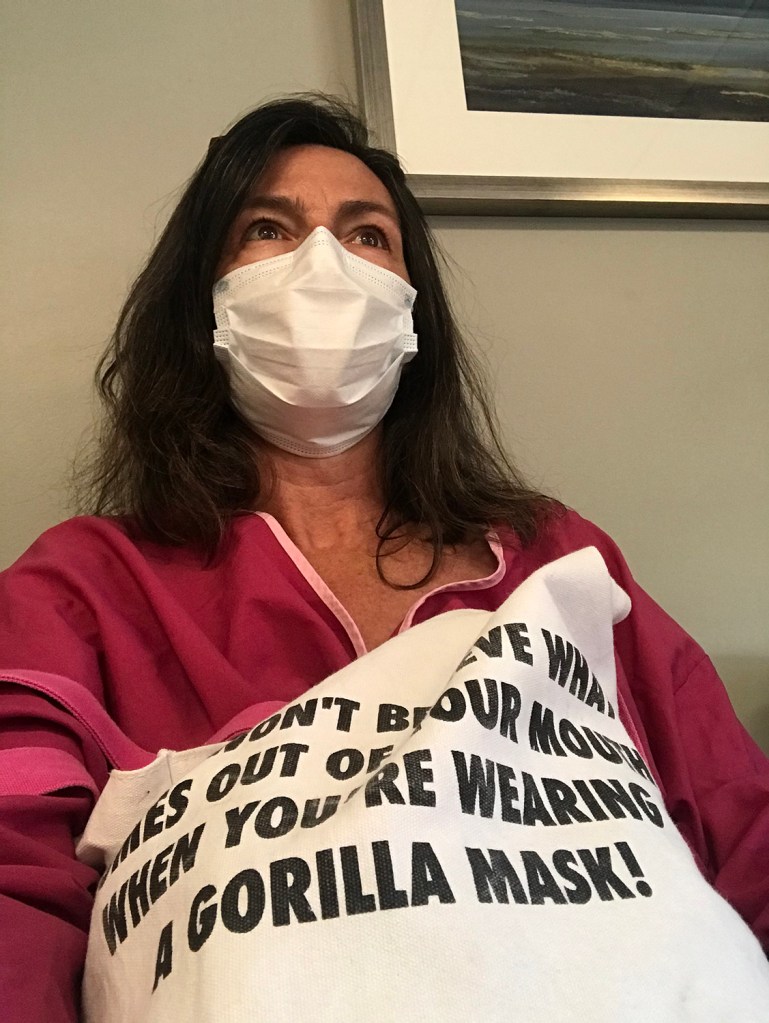

I arrived in Tucson after a long day of travel. The surreal experience of getting on a plane for the first time since the start of the pandemic was compounded by having to switch planes due to a mechanical problem and then, finally airborne, having a passenger with a serious medical emergency who was carted off by medics in Dallas. After a day of feeling pinned in a jam-packed plane, doubting the wisdom of having ventured back into the world of commercial travel, I emerged into the Arizona air and breathed in the cleansing smells of creosote and sage.

Early the next morning, we set out on the road trip to Palm Springs. The closer we got to California, the more the green hues that dust the Tucson landscape were replaced by a drier, flatter, more desolate desert. We lost ourselves in conversation as the miles passed, and suddenly, about four and a half hours into our journey, I noticed we were almost out of gas. In the West you can drive for 2 hours and see very little but sand, scrub, and dilapidated shacks, but after a knuckle biting 20-minutes, we found a truck stop and filled up for the final stretch. Soon after, the California mountains came into sight on the horizon.

We had only planned for a single night in California, so we headed straight to our first viewing: Kim Stringfellow’s Jackrabbit Homestead. The piece has taken multiple forms since its inception in 2009 (photography, a web-based multimedia presentation, and installation), all of which explore the Small Tract Act of 1938. The act held that federal lands deemed worthless could be made available for leasing for private homesteads. The act was different than the Homestead Act of 1862 in that it was designed to help veterans move west for health reasons, particularly those who were suffering from lung issues due to their service in WWI. Few were successful in maintaining their plots, and one can still see the deserted shells, known as Jackrabbit Cabins, in the landscape.

For Desert X, Stringfellow addresses this history through the construction of a small building evocative of a Jackrabbit cabin. The piece, through an audio component, draws on the writings of Catherine Venn Peterson, who scribed her homesteading experience in the 1950s. The Palm Springs cityscape where the piece is installed has been taken over by big box stores and so the structure underlines the shifting relationship with the land when placed in the context of this redundant urban setting, one we see on the edges of every city in the country. There was a voyeuristic pleasure in peeking into the windows to discover a typewriter with a poem-in-progress and a stack of wolf drawings.

Next, we headed over to the Desert X hub, a small room set behind a hotel pool jammed with imbibing sunbathers. As we picked up a map, one of the hub attendants said: “Go to Ghada Amer! It’s only open till 4:00 and this is the last day to see it. You don’t want to miss Ghada Amer!” We retraced our drive to the Sunnylands Center & Gardens to check out Women’s Qualities.

Amer’s piece was first created in 2000 and has taken a few different forms in the intervening years. The template for the work is letter-shaped metal containers that serve as planters for a range of flowers and greenery, each chosen to signify the words that they spell out on the landscape, in this case: loving, nurturing, resilient, strong, caring, determined, and beautiful. To generate the text for the work, Amer interviewed people on the street, asking them about the qualities they associate with women. Though the work has been popular and favorably reviewed, I was disappointed. The piece may, in its iterations over 21 years, speak to shifting traits associated with the feminine, but it still feels blunt. If there is intended irony—a consideration that ideals around gender association are detached from the actual experience of being a woman—it doesn’t come through in the actual work. The essentialist reading is still the strongest one, and it feels thin, as if what could be a powerful echo of 70s feminist practice (core imagery, the use of the decorative for fine art practice) doesn’t fully step up to address the complex ways that we now understand gender.

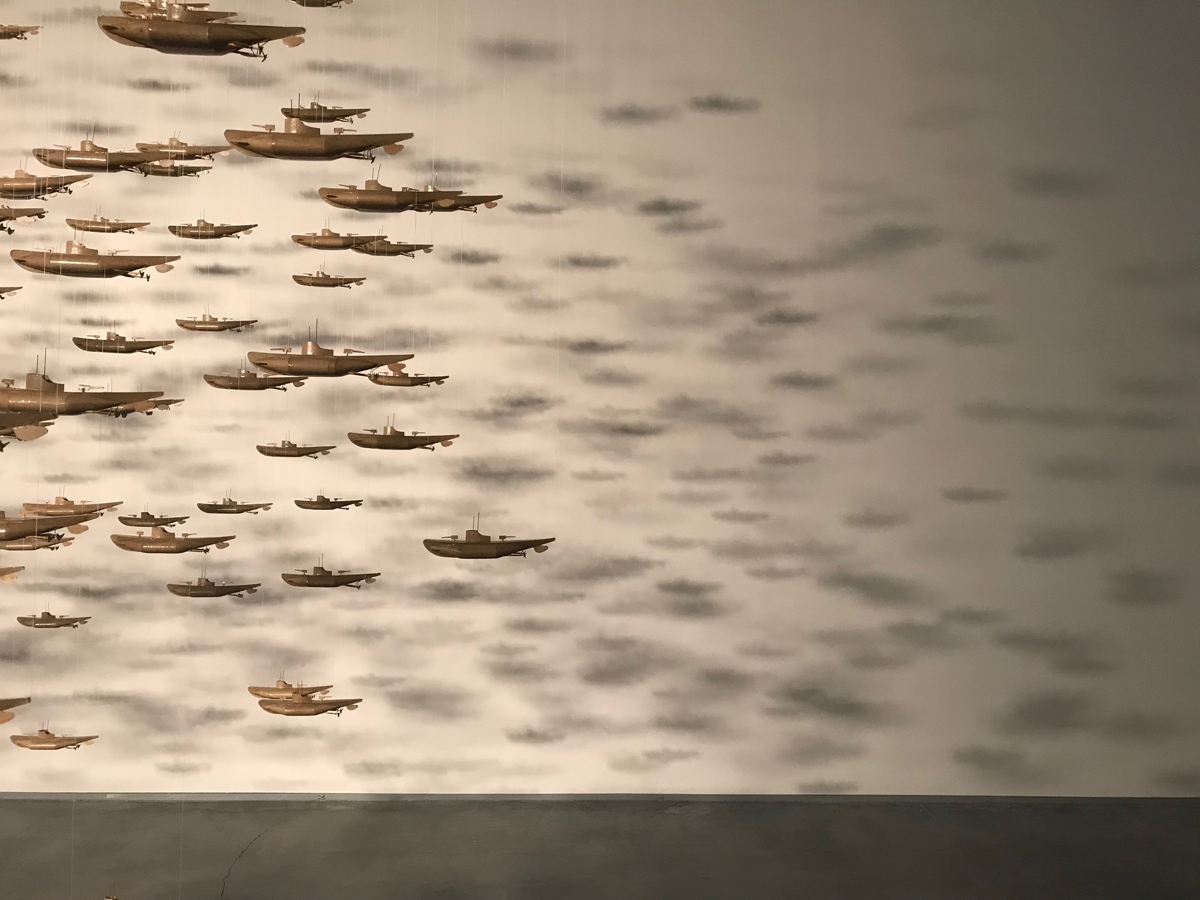

Next, we navigated to Eduardo Sarabia’s The Passenger, an arrow-shaped labyrinth, with walls made of woven palm petates. The trek across the hot sand to the installation site set the perfect context for reading the work. As I made my way across the hot sand, I imagined the much vaster, threatening landscape that some migrants experience–a visceral counterpoint to the rarified culture of an art biennial.

Sarabia’s parents migrated from Mexico in the 70s, and considerations of border politics are embedded in the work. As I wound my way through the labyrinth, the fiber walls provided a shelter and a path–danger and protection as dual sensations and dual readings. At the center of the labyrinth, platforms were constructed in each corner of the triangle where one could climb up and view the vast desert and distant horizon. As I looked around at the other visitors, it was clear that these platforms had also become selfie stages. That was a common Desert X sight, though not unique to this show; art as social media prop has become a common if somewhat surreal component of public art.

With the sun low on the horizon, we made our last stop of the day: Nicholas Galanin’s Never Forget. I’d met Galanin, a Tlingit and Unangax multimedia artist, years earlier at the Nevada Museum of Art’s triennial Art + Environment conference, and this spring, he was a visiting artist at MassArt, where I work as Dean of Graduate Studies. When Galanin made his virtual visit this spring, his Desert X piece had yet to be revealed, and I was eager to see what his contribution would be. The piece is set at the edge of the city, where the desert begins its rise into a small mountain range. INDIAN LAND is spelled out in the landscape in 45-foot letters, mimicking the classic HOLLYWOOD sign. In the 1950s and 60s, Palm Springs was a destination for (largely white) Hollywood stars, and with that simple reference, Galanin’s work makes visible the layers of colonization of the southwestern landscape, culture, and people. Galanin is refreshingly pointed and direct when he talks about the historical violence of colonial America and the continued pervasiveness of white settler mythologies, and the work is equally direct. Never Forget is a straightforward piece, but its physical impact, when you’re standing underneath the towering letters, is poignant. The piece has a sister project, a Land Back Go Fund Me site, where you can donate toward the goal of $300,000 to buy back a plot of land for indigenous nations, “to counter the devastating effects of colonization and settlement.”

From its presence on social media, it seems as if Never Forget has become a mecca of sorts. It’s easy to find social media documentation of sacred dancing and community sharing in front of the work, and in fact, there were a few native families gathering near the work as my mom and I left, and it felt right to slip away and make space for their experience.

Two of the Desert X installations are in Desert Hot Springs, and my mom and I decided to stay nearby so we could catch the two outliers early on day 2. The plan had been to find a restaurant nearby, where we could share a casual Mother’s Day dinner, but when we arrived, hot and tired, we found Desert Hot Springs to be a dark and depressed town. With trepidation, we navigated through the boarded up downtown and up a winding road to our hotel, Sagewater Spa. We arrived to a locked door but discovered a lockbox with an access code for our keys. After a bit of fumbling, we were surprised to find a small, lovely renovated hotel, with a handful of rooms lined up along a private pool. The rooms were clean and comfortable, with a mid-20th century modernist vibe. We settled briefly and then headed out to find food. After realizing that the complete range of options were KFC and McDonalds, we went to the grocery store and gathered beer, cheese, bread, smoked salmon, and hard-boiled eggs, and went back to the hotel for what turned out to be a relaxing, delicious feast, followed by a hot tub in the mineral water the area is known for.

The next morning, we packed up and headed out for day two of Desert X viewing. Our first challenge was in finding Alicja Kwade’s ParaPivot. We arrived before the piece was technically “open,” though exhibition hours weren’t evident from the parking lot. A handful of other visitors were wandering around looking for the work, and as we began poking around, they were giving up and hopping in their cars. Clearly, this had been an issue for the duration of the show, as there were hand-scrawled signs on nearby driveways: “This is not Desert X!” In the natural spot for our ascent to the work, there was a concrete road, but it was blocked by a metal gate, posted with “private property.”

We were determined, and began winding our way around and up the mesa on desert paths, trying to avoid barking dogs. As we approached the height of land, we had a sense we were headed in the right direction, if not on the prescribed route. We began to wonder if that might be the point.

It was a steep climb in the heat, and in the final stretch we had to bushwhack to avoid an abandoned shell of a house with an old RV parked outside. Eventually, I saw the sculpture rising up ahead, and felt a thrill of anticipation.

The piece is smart and gorgeous, as Kwade’s work tends to be. It evokes a disorienting sense of one’s precarious position between earth and sky. The marble blocks, edged into interlocking metal frames, feel simultaneously astronomical and glacial. Blocks of ancient ice (marble) are placed in relief against the blue expanse of southwestern sky.

From the site of the work, it was easy to see that a cement road had been constructed for the installation, no doubt at great expense. It was on the opposite side of the mesa from our trip up, and we made our way down easily, noting the strangeness of a cement road plunked down in the rough landscape. We quickly came to the fence that had blocked our way and after navigating around it, we began to notice that signs advertising a 7-acre plot of land for sale, by Desert X, dotted the parking lot.

As we drove away from the site, I called the number on the sign, curious if it was part of the work or a true real estate ad. “Hello?” a man with a Latino accent answered, and I inquired whether the land was really for sale. He said that Desert X had leased the land, and that, “the art work’s not for sale, but the land is.” On route to the next piece, mom and I chatted about the complex economic realities of destination exhibits, the expense of creating the work, and how the link to big name brands (Gucci and North Face, in the case of Desert X) underscores a little understood aspect of the high-end business of art.

The second piece in Desert Hot Springs was Zahrah Alghamdi’s What Lies Behind the Walls, and getting close to the work involved a quarter mile or so of navigation up into the foothills.

The rectangular wall loomed increasingly larger as we made our way up. The ochre, umber, and burnt sienna palette of the piece evokes geological strata, and from a distance the work felt monumental and rock solid, but as the installation came into focus, it was a delight to discover something more intimate and temporary, more like a gigantic stack of folded fabric than a wall of stone. As we circled the work, we could see that the materials—foam sprayed with dyes, soils, and cements–had frayed in places, weathered during the run of the exhibit. One might think that the “fake” of the wall–when one discovers that its materials are light and temporary and only an illusion of something monumental–might make the work seem thin, but its faux monumentality isn’t disappointing; it’s a discovery that forms the heart of the work. The discordance of form and function create a slow reveal that make the work spot on for current conversations about scale, monumentality, and the significance of walls in the American southwest.

The last work we saw was Attukwei Clottey’s The Wishing Well, an installation of large modernist cubes crafted from the yellow plastic used in water-carting jugs in Ghana. Though less formally transporting, the work had a similar resonance to Sarabia’s installation, underlining issues of power and oppression through the lens of access to water and the laborious process many communities around the globe go through to gather this essential resource. The work stands in juxtaposition to the profligate use of water that enables urban development in the arid American west.

There were a few works that seemed out of place in the exhibit, including Vivian Suter’s paintings and Christopher Myers The Art of Taming Horses. The former could be engaging in a gallery or museum context and the latter, which is installed near the airport and difficult to view, didn’t add much to a show with such lofty aspirations for social engagement. I was also disappointed to learn that Judy Chicago’s piece, Living Smoke: A Tribute to the Living Desert, had been cancelled, and we missed the work by Filipe Baeza, Oscar Murillo, and Xavieira Simmons.

I left the Desert X exhibit thinking about how we overuse the word monumental in writing about art. I’ve been contemplating the relationship between monumental, as an artistic strategy that references scale or impact, and monument, a sculpture or architectural structure that serves as a memorial to a person or event. Artists and art critics use monumental to describe a physical attribute but also to elevate the grandeur and importance of a work. Is this completely disentangled from the monuments that litter the world–art objects designed to elevate the powerful, and in many cases, intentionally signifying ownership of and power over? Of course, there are monuments that capture the complexities of loss–Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial being one of the best known–but the versions that are both bad art and propaganda for the powerful are much more common. I’m not suggesting that “monumental” be banished from the art criticism lexicon, but it should be considered carefully through the lens of the intent to create a sense of awe, of scale, that speaks to importance and value. Much of the work in Desert X successfully plays with the history of monumental work, using awe, surprise, and the playful experience of navigation as strategies for inspiring the viewer to think about her relationship to the historical and future landscape.

scattered about, and young climbers laden with crash pads heading in to boulder. Everyone was spread out and enjoying the fresh air. It’s a scary time, to put it mildly, but seeing kids hiking and exploring the woods is always a hopeful sight.

scattered about, and young climbers laden with crash pads heading in to boulder. Everyone was spread out and enjoying the fresh air. It’s a scary time, to put it mildly, but seeing kids hiking and exploring the woods is always a hopeful sight.

The first guy I passed, on his way out, was a bit of an exception. He looked fictional–long, combed hair and a wooden walking stick, metal water bottle tied to his belt–he was in his own world and didn’t acknowledge my presence as I passed. I waved to his silence. A mile or so later, I came up behind a young man with a camera in hand. He was bright eyed and friendly. We exchanged a “Happy New Year!” and “What a beautiful day!” as I ran by. About a mile and a half in, I came across a middle aged couple, walking down and looking elated. I asked how many miles it was to the summit–was it 4? They said that sounded about right, but that they’d had lunch at

The first guy I passed, on his way out, was a bit of an exception. He looked fictional–long, combed hair and a wooden walking stick, metal water bottle tied to his belt–he was in his own world and didn’t acknowledge my presence as I passed. I waved to his silence. A mile or so later, I came up behind a young man with a camera in hand. He was bright eyed and friendly. We exchanged a “Happy New Year!” and “What a beautiful day!” as I ran by. About a mile and a half in, I came across a middle aged couple, walking down and looking elated. I asked how many miles it was to the summit–was it 4? They said that sounded about right, but that they’d had lunch at  around 2.25 and turned around due to the intense wind. They mentioned a big pine that had fallen across the road, cautioning, “Don’t get hit by a falling tree out there!” The wind was getting more intense, noisy in the tree tops, but I figured I’d still head for the summit. I did come to the tree the couple had mentioned, but snow was covering the root ball, so it wasn’t freshly fallen. There was another tree down near the upper parking lot, easy to scramble over and again, not freshly fallen.

around 2.25 and turned around due to the intense wind. They mentioned a big pine that had fallen across the road, cautioning, “Don’t get hit by a falling tree out there!” The wind was getting more intense, noisy in the tree tops, but I figured I’d still head for the summit. I did come to the tree the couple had mentioned, but snow was covering the root ball, so it wasn’t freshly fallen. There was another tree down near the upper parking lot, easy to scramble over and again, not freshly fallen. windy and isolated. There were no human prints, but I did see what looked like moose tracks crossing back and forth. I also saw some large round prints covered by snow. The bears are likely hibernating, but I peered into the woods anyway, wondering…

windy and isolated. There were no human prints, but I did see what looked like moose tracks crossing back and forth. I also saw some large round prints covered by snow. The bears are likely hibernating, but I peered into the woods anyway, wondering…

Marathon

Marathon

For four years I’ve been running with the Maine Road Hags, an all-women’s team that competes at the

For four years I’ve been running with the Maine Road Hags, an all-women’s team that competes at the

nowhere. We headed along the rural road, fingers crossed, with the car reading “_ _ _ to empty.” I’ve never been so happy to see a gas station come into view, and now I know that you can get about 5 miles with _ _ _ in the tank!

nowhere. We headed along the rural road, fingers crossed, with the car reading “_ _ _ to empty.” I’ve never been so happy to see a gas station come into view, and now I know that you can get about 5 miles with _ _ _ in the tank!

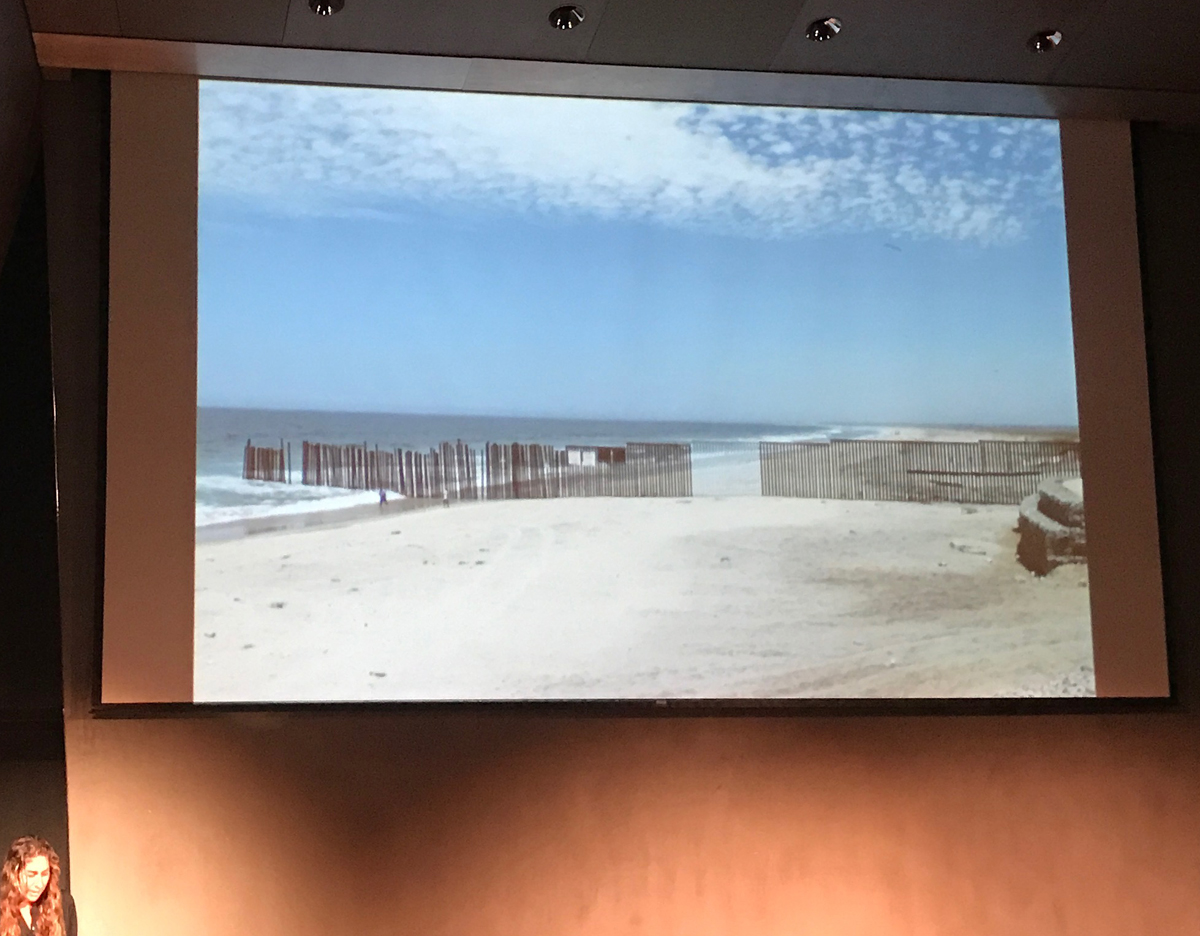

define us. She asserted that the power to make change in the world exists on these edges–that geographies can provide a locus for radical making and re-thinking. To my mind, this builds on theories from gender and identity politics, where the position of the Other can be a stance of witness, critique, and change-making.

define us. She asserted that the power to make change in the world exists on these edges–that geographies can provide a locus for radical making and re-thinking. To my mind, this builds on theories from gender and identity politics, where the position of the Other can be a stance of witness, critique, and change-making. the main auditorium remotely. Each day concluded with a reception and performance on the roof deck, and at the end of the first day, I was chatting away with a friendly man on the deck, about the museum’s stunning architecture. After 10 minutes of conversation, I introduced myself, only to learn that I was chatting with the building’s architect, Will Bruder! One of the most enjoyable aspects of the conference is the fact that programming is all shared (no concurrent sessions), and at the same time, there are multiple ways to engage; the building is designed to support a fluid experience. There are viewing rooms for study groups (a group of STEAM educators, in this case), the rooftop lounge, with couches and cushioned seats, and then the intimate auditorium itself. The exhibitions are installed on the floors in between, so one can dip in and out, taking in the work over the span of the conference.

the main auditorium remotely. Each day concluded with a reception and performance on the roof deck, and at the end of the first day, I was chatting away with a friendly man on the deck, about the museum’s stunning architecture. After 10 minutes of conversation, I introduced myself, only to learn that I was chatting with the building’s architect, Will Bruder! One of the most enjoyable aspects of the conference is the fact that programming is all shared (no concurrent sessions), and at the same time, there are multiple ways to engage; the building is designed to support a fluid experience. There are viewing rooms for study groups (a group of STEAM educators, in this case), the rooftop lounge, with couches and cushioned seats, and then the intimate auditorium itself. The exhibitions are installed on the floors in between, so one can dip in and out, taking in the work over the span of the conference.

given the power of the video, but perhaps it answered some formal drive for the artist. Fernandez was challenged during the QnA on her choice to wear heels and a tight black dress in the work. For her, the heels are key, she said, in that they reference the influence of tango dancing, as well as her experience in Mexico, where women are silenced at the table, but when they go out on the town, they’re “loud with their bodies.” For her, the tango, heels and all, is a superhero stance, and outfit, that fits her border project.

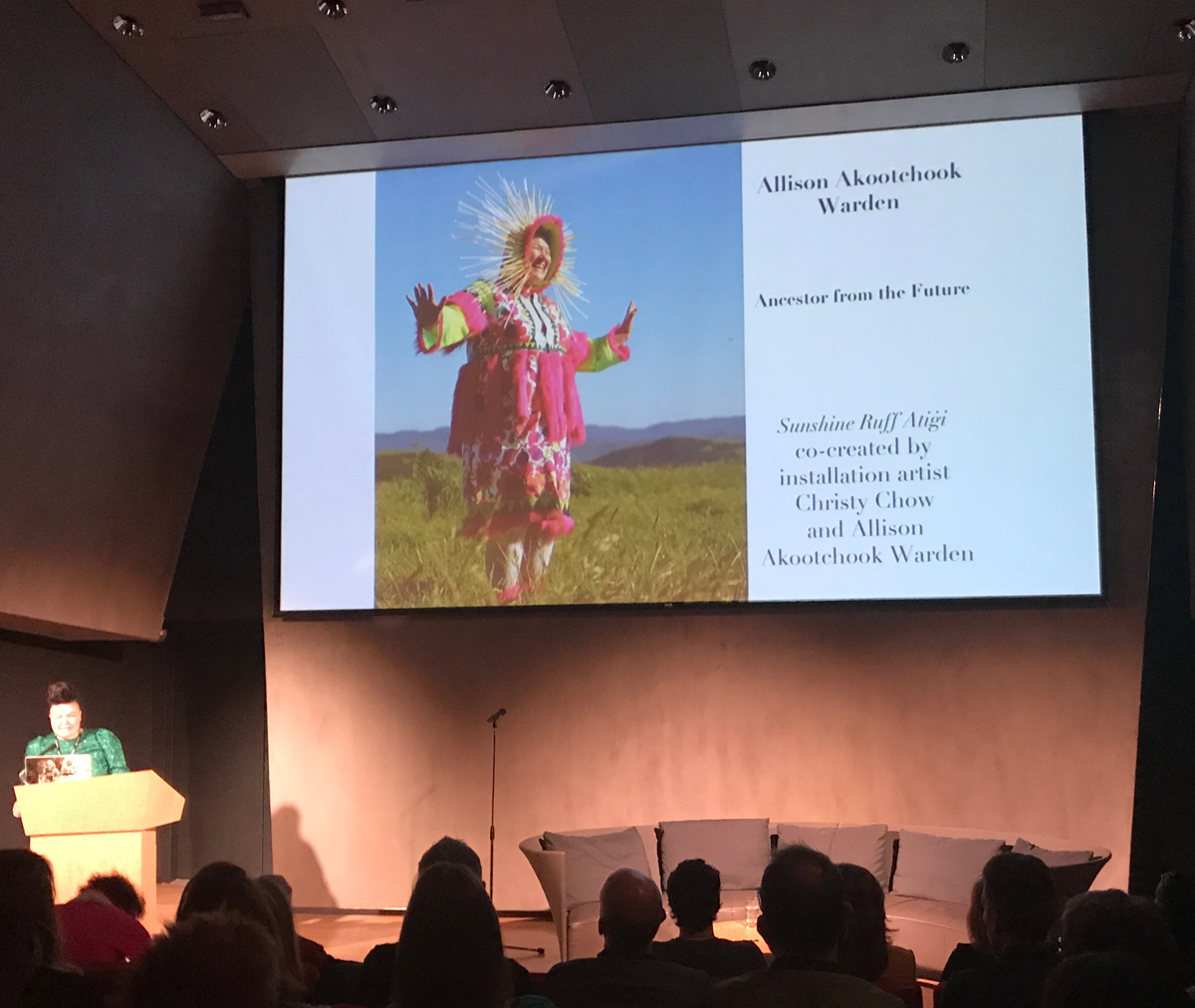

given the power of the video, but perhaps it answered some formal drive for the artist. Fernandez was challenged during the QnA on her choice to wear heels and a tight black dress in the work. For her, the heels are key, she said, in that they reference the influence of tango dancing, as well as her experience in Mexico, where women are silenced at the table, but when they go out on the town, they’re “loud with their bodies.” For her, the tango, heels and all, is a superhero stance, and outfit, that fits her border project. A high point of the conference and exhibit were the contributions by contemporary indigenous Alaskan artists N

A high point of the conference and exhibit were the contributions by contemporary indigenous Alaskan artists N performance, slipping seamlessly from artist’s talk into personas that were radical and contemporary while drawing on traditional cultural vocabularies. The group as a whole made clear the problem of romanticizing or pigeonholing what it is to be indigenous. As Galanin said: “Anthropology has homogenized the culture.”

performance, slipping seamlessly from artist’s talk into personas that were radical and contemporary while drawing on traditional cultural vocabularies. The group as a whole made clear the problem of romanticizing or pigeonholing what it is to be indigenous. As Galanin said: “Anthropology has homogenized the culture.” Several months ago, I participated in a storytelling festival at

Several months ago, I participated in a storytelling festival at  hill, given my upcoming

hill, given my upcoming  pressed my hand to my forehead and felt that it was wet. One of the guys took a look and said, “Uh oh, not good.” Michael handed me his buff, and I pressed it against the wound. I could feel the blood pumping and knew I had to get my heart rate down and get out of the woods. Jeff pulled off his sweat-soaked shirt and wrapped it tight around my head so the pressure would limit the bleeding, and we started walking out as a group. We were over a mile in so it took a while to trek out. I hadn’t blacked out or seen stars, but I had taken a hit to the head. I didn’t feel like I was getting loopy or about to pass out, but just in case a concussion was about to manifest, we exchanged some key phone numbers, and I let them know where my car key was. We began strategizing for how to get me to the hospital, as it was pretty clear stitches would be in order. Every person in the group stuck with me, offering support and distraction on the way out. Kate and I exchanged tales and started laughing about the ridiculousness of the situation. I couldn’t stop apologizing for interrupting their run, insisting, “I never fall!” “I run trails all the time!” “This isn’t my first rodeo!”

pressed my hand to my forehead and felt that it was wet. One of the guys took a look and said, “Uh oh, not good.” Michael handed me his buff, and I pressed it against the wound. I could feel the blood pumping and knew I had to get my heart rate down and get out of the woods. Jeff pulled off his sweat-soaked shirt and wrapped it tight around my head so the pressure would limit the bleeding, and we started walking out as a group. We were over a mile in so it took a while to trek out. I hadn’t blacked out or seen stars, but I had taken a hit to the head. I didn’t feel like I was getting loopy or about to pass out, but just in case a concussion was about to manifest, we exchanged some key phone numbers, and I let them know where my car key was. We began strategizing for how to get me to the hospital, as it was pretty clear stitches would be in order. Every person in the group stuck with me, offering support and distraction on the way out. Kate and I exchanged tales and started laughing about the ridiculousness of the situation. I couldn’t stop apologizing for interrupting their run, insisting, “I never fall!” “I run trails all the time!” “This isn’t my first rodeo!” and I’d sprained 3 fingers on my left hand. I was banged up, but cleared to drive home.

and I’d sprained 3 fingers on my left hand. I was banged up, but cleared to drive home.