A challenging race is a mind and body recalibration, and after this last year, with  multiple new jobs, border running, a solo exhibition, and the holidays, not to mention the excruciating political season, I was overdue for a re-tuning. Taking the body to its physical limits strips everything else away; it’s an escape but also a sharpening. After wrapping up the NHIA MFA residency in mid-January, I flew out to Tucson with my son for a family visit. I like to look for destination races when I’m traveling, and if there’s something interesting, I fit it in. With a quick web search, I found a new ultra-trail running series in Oracle, and I signed up for the half-marathon.

multiple new jobs, border running, a solo exhibition, and the holidays, not to mention the excruciating political season, I was overdue for a re-tuning. Taking the body to its physical limits strips everything else away; it’s an escape but also a sharpening. After wrapping up the NHIA MFA residency in mid-January, I flew out to Tucson with my son for a family visit. I like to look for destination races when I’m traveling, and if there’s something interesting, I fit it in. With a quick web search, I found a new ultra-trail running series in Oracle, and I signed up for the half-marathon.

On the morning of the race, I woke up in the dark, forced some oatmeal down, and hopped into the car with my mother to make our way up to Oracle, about 45 minutes from the Tucson foothills. A few miles from the park, we made a Circle-K pit stop. It was 6:45 a.m., and the place was hopping with runners and hunters–the runners on route to experience the wildlife refuge and the hunters heading elsewhere to “cull coyotes.” We made our way to the Justice Court and picked up the shuttle to Oracle State Park. The park covers 4,000-acres in the Catalina Mountains, and serves both as a wildlife refuge and as a center for environmental education (watershed, geology, topography, wildlife, etc.). We scrambled out of the van, breath in frozen clouds. Organizers were just starting a fire and had an outdoor propane heater cranking. I quickly picked up my timing chip and headed for the warmth. My fingers were already turning white with Raynaud’s syndrome, and I held them out to absorb the heat. The welcoming fire, with a big stack of wood that would last through the day, was the first sign that this would be an organized event, and it was, from start to finish.

As the sun rose, Mom and I chatted around the fire. Most runners were layered up, but I stripped down to ¾ length tights, ankle socks (for cholla and prickly pear defense), a light tech t-shirt, arm warmers, gloves, and a lightweight hat. This turned out to be perfect–adaptable as the sun started heating up the more exposed stretches of desert. I took off for a quick warm up, then to the road to gather with the other racers. The ultra series was sold out at 300 runners (10K, half, 50k, and 50 mile), and there were about 100 clustered on the road for the half.

On GO, the mass of us started down the blacktop toward the trail head. After about 20 yards, we ran single file onto a trail overhung with mesquite trees and juniper bushes. I passed a handful of people when I could, and ended up locked in with a group of 5, three women in front of me and two men behind. I was worried that the hilly course and technical footing would wipe me out, and I was happy to find a race posse that would rein in my early pace. The five of us chatted—each of us using the conversational pace both as a strategy and to pass the time. About a mile in we came over a rise and down into a frost-licked dip. At the base, I noticed a set of huge cat prints in damp sand. “Fresh tracks!” said one of the guys behind me.

“Bobcat?” I asked.

He chuckled, “That was a puma!”

A little further in we saw javelina tracks, then smaller cat prints, and scat was visible along the trail throughout the race. It was a lively desert refuge, and clearly the path was convenient for all species!

The course was hilly from start to finish except for a few stretches in the middle and one near the end. A few miles in, the pace was still comfortable, and I pondered whether to pass and pick it up. Given the challenging trail, I decided to just hunker down and reassess in a few miles. The terrain changed frequently, and it was pretty hard to find a groove. I’ve only run one Southwestern trail race (the McDowell Mountain frenzy in 2013), and I fell forward hard in the last mile of that 10-miler. Since these trails were slippery with frost, mud, sand, pebbles, and diagonal rock waterbars–even one patch of snow–I stayed hyper-focused on placing my feet and not letting the growing aches in my legs make me sloppy. On the longer climbs, everyone in sight walked with quick steps, and I followed suit, trusting the more experienced trail racers.

About 4 miles in, we were on a grassy open plain, The trail had turned from dense cacti, creosote bushes, and palo verde to gorgeous grassland—golden light stretching out in all directions. One of the guys in back passed and took off. I followed his lead, a bit slower, passing 2 of the 3 women in front of me and locking in behind the leader of our pack. We ran together for a mile or so. She said I was helping to push her pace, but when we came to a relatively straight downhill stretch, I decided to pass and let the hill carry me down. I like to let it rip down the hills, though I’m guessing that’s why my legs are so sore post-race! Around 6 miles in, I ran down into a wash where I found the first of 2 aid stations. I was running with two water bottles and some Honey Stinger chews in an Amphipod belt, so I cruised by, turning right to climb on to a frost-covered trail. The trail eventually lead back down to the wash, which offered a mile and a half of flat, beachy sand. At that point I was completely alone in the race. I heard some rustles in the hills and glanced around a few times, remembering the lion tracks at the start. Eventually, the trail bumped back up to the left, and the rise and fall of hills started up again.

At 10 miles, the hills and technical running started to catch up with my legs. Even in the flat sections, I was entering survival mode. I’d be just hanging on for the rest of the race. At one point, a woman locked in behind me, sticking close through mile 11. I asked if she wanted to pass (the trails were often thin, rocky ditches surrounded by cacti). She answered, “Nope, you’re my pacer, and you’re fast on the downhills.”

“We’ll see how long that lasts,” I mumbled back. By the time we came  to the last wash, I felt like I was shuffling, just willing my legs move. She passed me at that point, keeping a slightly steadier pace than I could muster. I caught up to another guy in the wash. We’d passed each other a few times, and I felt sure he’d drop me, but he ended up falling back. Finally, the trail dipped down into a small picnic area, and I realized we must be getting close to the finish. I could hear cheering in the distance and determined to run up the last hill. As I came over the rise, I could see the finish line. I was so relieved, I thought I’d start crying. I stuffed the emotion down and stretched out my strides to the

to the last wash, I felt like I was shuffling, just willing my legs move. She passed me at that point, keeping a slightly steadier pace than I could muster. I caught up to another guy in the wash. We’d passed each other a few times, and I felt sure he’d drop me, but he ended up falling back. Finally, the trail dipped down into a small picnic area, and I realized we must be getting close to the finish. I could hear cheering in the distance and determined to run up the last hill. As I came over the rise, I could see the finish line. I was so relieved, I thought I’d start crying. I stuffed the emotion down and stretched out my strides to the  finish. I was beat!

finish. I was beat!

They handed me a finisher’s medal–a horseshoe on a leather thong–and asked if I was okay. I didn’t understand their concern until I saw photos of the finish. I  looked like my legs were going to give out any second! With difficulty, I hoisted my sneaker on the bench so they could cut off my timing chip, then greeted my mom, who had gotten into her role as pit crew, maintaining the fire throughout most of my 2:20 on the trail. After grabbing a drink and banana, I looked at the results and was shocked to see that I’d finished fourth for the women overall. The first three were in their 20s and 30s, and unfortunately, there were no masters awards (40 and over). Still, it was a great event with great energy and something for everyone—from the 10K first timer to the ultra-fanatic.

looked like my legs were going to give out any second! With difficulty, I hoisted my sneaker on the bench so they could cut off my timing chip, then greeted my mom, who had gotten into her role as pit crew, maintaining the fire throughout most of my 2:20 on the trail. After grabbing a drink and banana, I looked at the results and was shocked to see that I’d finished fourth for the women overall. The first three were in their 20s and 30s, and unfortunately, there were no masters awards (40 and over). Still, it was a great event with great energy and something for everyone—from the 10K first timer to the ultra-fanatic.

Writing these play-by-play race reviews reminds me of why pushing my body to its limits feels like a release—everything is reduced to the choices, relationships, and narratives of the experience. A group of runners finds each other based on pace, and they talk about mountain lions, racing, beer, the landscape, and running strategies. Then there’s a stretch of solitude, where the sensations, sounds, and smells take over, where the runner focuses on her movements, assessing the state of exhaustion through each quadrant of the body: mind, legs, lungs, core, arms, feet… And then there’s survival, where she simply thinks about the diminishing time and distance, asking legs and lungs what they have left in the tank. She thinks about things that inspire her, of coaching wisdom, and occasionally her mind wanders, but mostly she just lives in her body and takes in the view when she can. Particularly given the precarious state of the world, I’m grateful that places like Oracle State Park exist–monuments to nature’s diversity, to human care that stretches beyond greed, and to the opportunity that such a place offers to experience one’s limits in the face of the wild and unexpected.

(gathering and contributing soil for a previous biennial), but this was the first installation I was able to see in person.

(gathering and contributing soil for a previous biennial), but this was the first installation I was able to see in person.

and that knowledge—just as a context, without awareness of any specifics—caused me to feel my body in the space in a conscious way. And given the current wave of people outing their stories of abuse, as a way to speak truth to the dark misogyny of the Republican Presidential candidate, I found the simple act of pressing my finger into clay to be emotionally difficult. And from that mid-point in the exhibition, I entered some liminal state where the history of my own body moved through the space with me.

and that knowledge—just as a context, without awareness of any specifics—caused me to feel my body in the space in a conscious way. And given the current wave of people outing their stories of abuse, as a way to speak truth to the dark misogyny of the Republican Presidential candidate, I found the simple act of pressing my finger into clay to be emotionally difficult. And from that mid-point in the exhibition, I entered some liminal state where the history of my own body moved through the space with me.

memories of swimming across, horrible border crossing tales (lots of those), cultural experiences that question the border altogether, and family immigration stories, among many others. I quickly realized that rather than following the 611 mile map along the Maine-Canada border, I’d be jumping around from point to point, following people’s stories. The idea of privileging chance process over a pre-established order felt creatively right as well, and so I’ve spent the year engaging in dialogue with a wide range of people from around the state, all with very different understandings of border and boundary, both conceptually and in terms of the Maine border. The spirit of the Kindling grant is collaborative, and the granting agency holds an expanded understanding of audience and venue; my shift in approach also seemed more deeply aligned with that vision. This approach to process continues to lead me into inspiring pockets of coincidence, and coincidence is what shows up when a creative project finds its roots.

memories of swimming across, horrible border crossing tales (lots of those), cultural experiences that question the border altogether, and family immigration stories, among many others. I quickly realized that rather than following the 611 mile map along the Maine-Canada border, I’d be jumping around from point to point, following people’s stories. The idea of privileging chance process over a pre-established order felt creatively right as well, and so I’ve spent the year engaging in dialogue with a wide range of people from around the state, all with very different understandings of border and boundary, both conceptually and in terms of the Maine border. The spirit of the Kindling grant is collaborative, and the granting agency holds an expanded understanding of audience and venue; my shift in approach also seemed more deeply aligned with that vision. This approach to process continues to lead me into inspiring pockets of coincidence, and coincidence is what shows up when a creative project finds its roots.

we learned that all 9 planets were placed along Rt. 1 in a 40-mile scale model of the Solar System: one mile along Rt. 1 equalling one astronomical unit (the distance from the Earth to the Sun). I remembered hearing about a road race that coincided with NASA’s

we learned that all 9 planets were placed along Rt. 1 in a 40-mile scale model of the Solar System: one mile along Rt. 1 equalling one astronomical unit (the distance from the Earth to the Sun). I remembered hearing about a road race that coincided with NASA’s  toward Madawasca, with the plan to have Rebecca scoop me up when I was finished. With unyielding trucks and slippery footing, it was a rough run, but I was able to witness the way the river creates a natural boundary between the two countries in that section of the border, and I could imagine people dreaming across the divide, in both directions.

toward Madawasca, with the plan to have Rebecca scoop me up when I was finished. With unyielding trucks and slippery footing, it was a rough run, but I was able to witness the way the river creates a natural boundary between the two countries in that section of the border, and I could imagine people dreaming across the divide, in both directions. Julie’s exhibit was powerful, based on Borges’ “The Library of Babel.” I’ve loved Borges since I read Labyrinths in college, so this seemed another appropriate coincidence. Julie’s work powerfully inspects language and meaning, storytelling and the experience of the body, the cerebral and the sensual, what is known and unknown (and the mysterious space in between). Truly multi-disciplinary, the exhibit incorporated text, performance, sculpture, and collaborative engagement, and provided another point of inspiration for my own project, particularly in thinking about how I would eventually represent my experiences in the form of art objects.

Julie’s exhibit was powerful, based on Borges’ “The Library of Babel.” I’ve loved Borges since I read Labyrinths in college, so this seemed another appropriate coincidence. Julie’s work powerfully inspects language and meaning, storytelling and the experience of the body, the cerebral and the sensual, what is known and unknown (and the mysterious space in between). Truly multi-disciplinary, the exhibit incorporated text, performance, sculpture, and collaborative engagement, and provided another point of inspiration for my own project, particularly in thinking about how I would eventually represent my experiences in the form of art objects.

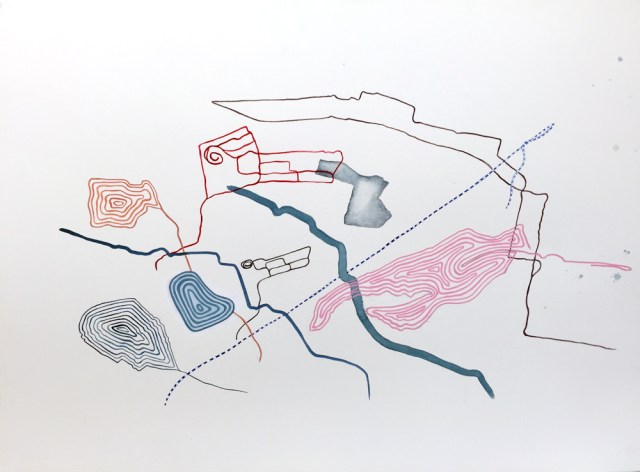

what might have happened if we’d gotten tired ten minutes later, or if I’d seen the marquis at the Bataclan and realized that the Eagles of Death Metal were playing (I’ve wanted to see them live for years and wouldn’t have missed it if I’d known). But I wasn’t there, and to fret about what if feels self-indulgent in the face of the hundreds of people who did stop for a glass of wine, or did see the marquis, and who were either killed or lived through horrors I can’t imagine. Nevertheless, the memory of that walk keeps showing up for me, and I’ve drawn the Endomondo map many times, incorporating it into multiple drawings–the simply looping line of our Paris walk signifying an unknowing turn away from horror.

what might have happened if we’d gotten tired ten minutes later, or if I’d seen the marquis at the Bataclan and realized that the Eagles of Death Metal were playing (I’ve wanted to see them live for years and wouldn’t have missed it if I’d known). But I wasn’t there, and to fret about what if feels self-indulgent in the face of the hundreds of people who did stop for a glass of wine, or did see the marquis, and who were either killed or lived through horrors I can’t imagine. Nevertheless, the memory of that walk keeps showing up for me, and I’ve drawn the Endomondo map many times, incorporating it into multiple drawings–the simply looping line of our Paris walk signifying an unknowing turn away from horror.

application. It seemed clear that my previous studio work focusing on the borders and boundaries of farms and watersheds would shift to a consideration of national borders. A month after my return to the States, I learned that I’d received

application. It seemed clear that my previous studio work focusing on the borders and boundaries of farms and watersheds would shift to a consideration of national borders. A month after my return to the States, I learned that I’d received

As I continued to meander the grounds, I started thinking about classical models of architecture and design–how that application of proportion relative to the human body works, literally works, vibrating through the body with a balance of form, light, and negative space. At the same time, the authority signified by that very kind of structure points to the darker history of domination and oppression. I remain in awe of Monticello and fascinated by the contradictions it embodies. I’m holding in mind the more than 200 slaves that lived, worked, gave birth, and died in service of one man’s brilliant, complicated interpretation of classical and humanist ideals.

As I continued to meander the grounds, I started thinking about classical models of architecture and design–how that application of proportion relative to the human body works, literally works, vibrating through the body with a balance of form, light, and negative space. At the same time, the authority signified by that very kind of structure points to the darker history of domination and oppression. I remain in awe of Monticello and fascinated by the contradictions it embodies. I’m holding in mind the more than 200 slaves that lived, worked, gave birth, and died in service of one man’s brilliant, complicated interpretation of classical and humanist ideals.

. On day 2, people began to venture out, and I decided it was time to take a run and get a feel for state of the city. I left the hotel and made an 8-mile lollipop loop from the Latin Quarter to the Eiffel Tower, along the Seine, and back down by the Luxembourg Gardens. It felt good to see other runners out there and to share that runner’s glance as we crossed paths. Those of us who made it out that morning, offered nods of acknowledgement as we passed: Yup, I’m out here too–pretty friggin’ scary but it feels good!

. On day 2, people began to venture out, and I decided it was time to take a run and get a feel for state of the city. I left the hotel and made an 8-mile lollipop loop from the Latin Quarter to the Eiffel Tower, along the Seine, and back down by the Luxembourg Gardens. It felt good to see other runners out there and to share that runner’s glance as we crossed paths. Those of us who made it out that morning, offered nods of acknowledgement as we passed: Yup, I’m out here too–pretty friggin’ scary but it feels good! On Monday afternoon, I ventured out with my mother to visit the Louvre, which, after three days closed for mourning (and security) had opened its doors. We waited in line as police and military with machine guns, fingers on triggers, strolled back and forth around us. The lines were huge, and organized in a big snaking coral. We’d been advised not to linger in large crowds but decided to queue up anyway, and spent an hour among the hushed crowd, inching toward the door. After making our way through security, the grand Louvre opened up before us. We spent the entire afternoon wandering through the museum, starting with the seemingly endless halls of paintings, stopping to linger in front of favorites. I could have spent all day in front of Vermeer’s Lacemaker of 1670; the piece is so perfect, it’s hard for the eyes to get enough of it. I was also struck by one of the temporary exhibits,

On Monday afternoon, I ventured out with my mother to visit the Louvre, which, after three days closed for mourning (and security) had opened its doors. We waited in line as police and military with machine guns, fingers on triggers, strolled back and forth around us. The lines were huge, and organized in a big snaking coral. We’d been advised not to linger in large crowds but decided to queue up anyway, and spent an hour among the hushed crowd, inching toward the door. After making our way through security, the grand Louvre opened up before us. We spent the entire afternoon wandering through the museum, starting with the seemingly endless halls of paintings, stopping to linger in front of favorites. I could have spent all day in front of Vermeer’s Lacemaker of 1670; the piece is so perfect, it’s hard for the eyes to get enough of it. I was also struck by one of the temporary exhibits,